Music plays a crucial part in bringing a game to life. We asked The Kraken Wakes's composers, John Matthias and Jay Auborn, about the inspiration behind the soundtrack, and the innovative “emotionally adaptive score” that has been developed for the game.

What’s unique about designing the soundtrack for a game, compared to a film or TV show?

A film is typically a fixed media work: once it’s locked for the music, sound design and audio effects to be added, the scenes and edits don’t change (usually!). Games are very different. They’re non-fixed media works: they’re interactive, the player often has the agency to decide where to go and what to do, and the duration is variable, often lasting several hours. Writing the score to a game is much more like writing what Umberto Eco called an “Open Work”, a musical work with many variations depending on context. This makes it very exciting, but also very challenging as composers!

What inspired the music for The Kraken Wakes?

The novel and the game are both set in 1950s England. We wanted the score to evoke this era without being overly pastiche. So, we asked ourselves what we’d have been listening to in the 50s, and what excited us about this period in music and art.

In the 1950s and 60s, several American composers, including Morton Feldman, John Cage, and Miles Davis with Gill Evans, were trying to define the sound of American music. The “classical” composers such as John Cage were reaching beyond the influence of the European giants and found a liberty in not having to continue a European compositional tradition. The classical music of this era in the US is heavily influenced by jazz, and also by new ideas from the 1920s and 30s such as graphic scores and improvisation. We’ve tried to think about a very British response to the music of the period – channeling Morton Feldman, say, via Ronnie Scott’s (the famous Soho jazz club), but tinged with Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippet, and also the watery worlds of several horror films.

Ronnie Scott’s, the Soho jazz club which formed part of our thinking about the soundworld of Kraken. Photo by N Chadwick. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Our conversations about music centered around: Rothko Chapel by Morton Feldman, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, by Alberto Iglesias, Concerto for Orchestra by Béla Bartók, Gayane Suite by Aram Khachaturian, The Thing theme music by Ennico Morricone, Become Ocean by John Luther Adams, The Disintegration Loops by William Bassinski, and our own soundtrack to In the Cloud.

What were the different stages in creating the score for Kraken, from composition to implementation?

Initially, we talked a lot about the “soundworld” we were going to create. The term “soundworld” describes any instrumentation and production ideas that contribute to the overall sound present in a score. Just as it’s important for a game to have a consistent visual style, it’s also important for it to have a consistent soundworld: it gives the game continuity and helps to immerse the player. To create our soundworld, we began by building a playlist of instruments and tracks which we thought could be used as references to create our soundworld.

We then worked with a set of visual mock-ups from the game which we used as a kind of animatic (a sequence of stills used before an animation is created). This gave us a process for playing musical ideas alongside the visual world which was going to be created for the game.

The Kraken Wakes takes its player to a wide range of locations, from tropical beaches to coastal cottages. It was decided that we’d create a musical theme for each key location in the game. Each theme would need to adapt to the real-time emotional states of the characters, and also to the amount of decay present in the environment. As the Kraken invasion escalates and the sea levels rise, the world around the player begins to fall apart – and with it, the music also undergoes a transformation.

The first piece we composed for the game was the EBC office theme. This involved both of us improvising ideas around the piano, adding drums and then bass once we were happy with what we’d recorded. We tend to work with acoustic instruments. This is unusual in game composition, for which composers tend to work with samples and available virtual instruments. The acoustic route presents much more of a challenge for an adaptive score, as each variation in the music is a new discrete recording, but we think it makes the soundtrack more authentic and unique.

The implementation of the music was dictated by our Emotionally Adaptive music system – more on that in just a moment!

Do you have a favourite piece of music – or musical effect – from the Kraken soundtrack?

John: I was really pleased with how the Cornwall Cottage theme came out. We’d written the EBC office theme in the key of C minor, and we changed to the relative E flat major for Cornwall Cottage, incorporating the same main theme tune, but creating a very different, bucolic atmosphere. This is a leitmotif technique explored a lot in film music in the mid-20th century, based on techniques developed in the 19th century post-Beethoven.

Jay: For me, a definite highlight was the unexpected outcome of processing the musical themes using damaged cassette tapes and underwater speakers to create the “decayed” versions. This was change in action, composition via process!

Tell us more about the decayed audio and the underwater recordings!

We described earlier how we wanted the music to break down along with the world of the game. Locations revisited by the player as the game progresses should feel familiar and, at the same time, jarring, distorted. To achieve this effect through the music, each theme has been increasingly processed using magnetic tape and water damage for different stages of decay.

Working with the team at dBs Pro, we devised two processes for distorting and decaying the audio of the game.

The first involved recording the music onto cassette tapes. Tape adds a nice warmth to the sound – less bright, with exaggerated lower mids. But it also introduces artifacts which begin to alter the music, such as distortions and subtle pitch variations. We overused and processed the music on tapes in order to bring the unwanted effects of the medium to the surface. This creates an eerie, nostalgic quality in the music, perfect for a sci-fi/horror game. We also used tape loops of odd lengths, which altered the musical phrasing of the original themes: the result is something familiar, yet different.

As the world floods around the player, we also wanted the music to take on an increasingly watery sound. To achieve this, we filled a tank full of water and submerged speakers into it at various depths. Then, using hydrophones (microphones for recording underwater), we played back the damaged tape versions of the music while moving the hydrophones around in the water. This creates a resonant, undefined, drone-like sound.

You mentioned the Emotionally Adaptive music system that has been pioneered for the game. What is it – and where did the idea come from?

Central to the whole vision for The Kraken Wakes is the player’s ability to influence the characters’ emotions, decisions, and relationships, all through what they choose to say. Our Emotionally Adaptive music system means that these player-directed changes of mood are also reflected dynamically in the soundtrack of the game.

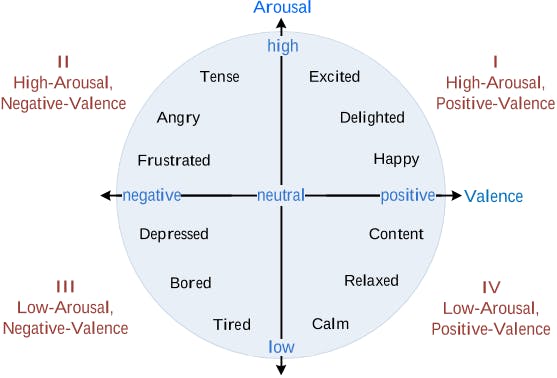

The thinking behind this system came from Patrick Juslin’s ideas about music and emotion, which have been developed in a series of academic papers by Juslin and collaborators since the early 2000s. Juslin’s ideas about emotions conveyed through music are based on the circumplex model of emotions developed by Russell, first published in the 1980s. In Russell’s circumplex model, emotions are conceived of as a two-dimensional space: on the X axis, we have “valence”, a spectrum of emotions running from negative to positive, and on the Y axis, we have “arousal”, or the intensity of the emotion being experienced:

Diagram showing circumplex model of emotions. Figure taken from Liu, Zhe & Xu, Anbang & Guo, Yufan & Mahmud, Jalal & Liu, Haibin & Akkiraju, Rama. (2018). “Seemo: A Computational Approach to See Emotions”.

We’ve adapted Juslin’s ideas to think about emotion in a game scene as a two-dimensional landscape (valence and arousal). We wanted each of our musical themes to be capable of varying according to both spectrums, becoming more positive or negative, but also more or less intense, depending on how player inputs are influencing character emotion. A character might feel sad – a negative, low intensity emotion – or they might feel angry – a negative, high intensity emotion. We wanted this nuance to be reflected in the changing soundtrack of the game.

That sounds very exciting – and very complicated! Can you tell us how it works?

It’s certainly been a challenge! In terms of composition, the Emotionally Adaptive audio system adds an extra layer of complexity, because several different pieces of music have to be developed for each theme. A theme might have three different emotional variations – negative, neutral, and positive – and as many as ten different variations of rhythmic intensity corresponding to the “arousal” spectrum – how intensely a positive or negative emotion is being felt. To enable continuity between these variations, we had to think very carefully about pace, key, instrumentation and timbre, to make sure that each theme could change seamlessly from one emotional state to another.

In order to implement the game’s adaptive soundtrack, we had to devise a system for tracking the emotional states of game characters and feeding this into a music middleware program called FMOD. We worked with the game’s narrative designer, Rianna, to understand what was driving the emotion in each scene. These variable emotions then had to be converted into numbers in order to be interpreted by FMOD. Giorgio Cortiana, who has overseen sound and music implementation, devised systems within FMOD to select and move between the available variations of the different themes in instrument groups, according to the emotion inputs it receives.

Of course, we don’t want each scene to begin from a neutral starting point, musically speaking. There are moments in the game when the music at the start of a scene – before any emotional variation – should already be positive or negative, calm or intense. We’ve therefore set it up so that the writers can set the starting levels for emotion and intensity at the beginning of a scene. The music will adapt from this starting point as the values for each scale increase or decrease – a kind of calibration.

Our ultimate goal is for the player to feel the impact of their words in the soundworld of the game. As you play The Kraken Wakes, you should be able to work out when and how the emotion is changing from the way the music changes – but these changes should also feel smooth, a dynamic, living soundtrack adapting to what you say and do.

Have you done anything like this before?

No – as far as we’re aware, what we’ve done in adapting Juslin’s methodology to interactive audio and music is completely new! Before Kraken, we did work in a team funded by the South West Creative Technology Network (SWCTN) on a prototype project called Mindflow, which measured arousal and valence using sensors on the body to adapt a piece of music in real time. So some of the seeds of our ideas for Kraken were sown then, but what we’ve created with Charisma is a truly innovative approach to interactive game audio.

Credits

The music for Kraken Wakes was written and performed by John Matthias and Jay Auborn

Production of audio, music, sound design and implementation has been overseen by the creative audio company dBs Pro.

Giorgio Cortiana for dBs Pro is the lead audio programmer.

Jay Auborn for dBs Pro is the audio director.

A team of sound designers and sound engineers from dBs Institute have worked on the project contributing original sounds and production processes.